Lavinia and I have decided to start a blog. If Duncan Green can do one then so can we. If it is half as good as his ‘Poverty to Power’ musings and attracts half as many visitors, then we shall both be well pleased.

The first blog post will tackle the complex question of ‘what is this governance thing anyway?’ I remain surprised how many times I am asked this question. I suppose it’s like most things; if you know which English King was married to Eleanor of Aquitaine, then question is pretty easy. If you don’t it’s tricky.[1]

De-bunking the ‘good’ governance myth

It is worryingly commonplace today to read claims, usually made by western politicians, that ‘good’ governance is necessary – even a pre-requisite – for all good things: poverty reduction, growth, development, peace and security.

David Cameron began talking about to a ‘golden thread’ of international development in 2006.[2] In 2012 he said that the UK’s role was to help the poorest countries “create the building blocks of private sector growth and prosperity”, blocks characterised by “no conflict, access to [free] markets, transparency, property rights, the rule of law, the absence of corruption, a free media, free and fair elections.”[3]

Mr Cameron has also placed independent judiciaries, rich civil society and effective public services at the heart of the golden thread narrative, as well as acknowledging the importance of human development (health, education) and gender in a comprehensive development vision. Clearly the implicit sub-test was that ‘they’ just needed to be more like ‘us’. In this vision, all good things come together. In a satisfying twist of fate, Mr Cameron found out in June 2016 that often it is bad things that come together, rather than good things, when he lost both the EU referendum and his keys to 10 Downing Street.

Few development practitioners or researchers subscribe to the idea of the golden thread. Staff in DFID certainly do not. William Evans and Clare Ferguson extensively researched the question and concluded that:

…. the evidence does not show that democracy is a cause of higher incomes. Nor does it show that higher incomes will automatically lead to democracy. There is some more convincing evidence that democracies are necessary for the maintenance of growth[4].

The evidence tells us that countries get rich first, then they get ‘good’ government, not vice-versa. The 21st century rich world (broadly speaking, OECD countries) did not first establish liberal democracy, free markets and merit-based public services and then acquire wealth.

On the contrary, much of Western Europe and the US industrialised behind high protective trade barriers using state intervention, and sometimes even expropriating massive profits from their empires. These governments were highly exclusive and more often than not relied on patronage. Fast growing European states in the 20th century were certainly not transparent or accountable.

The success stories of south-east Asia (Japan, Singapore, Korea, Taiwan, and latterly China and Malaysia) followed a similar path of state-led industrialisation under relatively authoritarian governments. Only once GDP figures climbed and a demanding middle-class emerged do we see movements towards greater popular accountability[5].

But of course….institutions are important

We do know however that institutions matter; indeed they are critical to the prospects for growth and development. Institutions are the formal and informal rules and norms that organise social, political and economic relations[6]. Institutions are not the same as organisations – organisations have budgets, walls, tables and chairs. Institutions can be formal (like constitutions or financial regulations) and informal (like shaking hands, using cutlery or time-keeping).

We also know that institutions are brought to life by people and organisations and who in turn are shaped by those institutions. We know that institutions provide a relatively stable structure for everyday life and human interaction – which explains why they change only slowly. We also know that institutions can produce positive and negative outcomes, dependent on the sorts of behaviour that they incentivise[7]. We know that in each specific country context, this mix of formal and informal institutions establish the ‘rules of the game’ that influence if not determine individual and collective behaviour. And of course it follows that the mix of institutions differs – often dramatically – in each country.

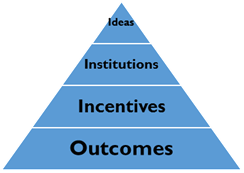

So just where do institutions fit in the long-haul struggle for change and progress? One of the clearest and most persuasive simplifications I have seen recently comes from a wonderful book by Wayne Leighton and Edward Lopez[8]. They suggest that starting point has to be a theorisation of how change happens. We know that one of the bedrock principles of economics is that incentives influence, if not determine, individual and collective decisions. The interplay of the total swirl of incentives influences the goods and services people buy, what entrepreneurs invest their money in, how people behave to one another, whether or not they obey the law, etc. In short, the aggregation of peoples’ interests influence outcomes. But incentives do not exist in a vacuum. They are themselves influenced by the wider array of formal and informal institutions that exist in any society. Institutions shape the structure and patterning of incentives, which in turn, over the long run, are shaped by ideas.

The figure on the right shows the relationship among ideas, institutions and incentives  that generate social and political outcomes. This is not a one way, top-down process. Institutions shape the structure and patterning of incentives, which in turn, over the long run, are shaped by ideas. Institutions are both the product of, and in turn shape, ideas and what is socially and politically ‘the conventional wisdom’ – until ideas have shifted to the extent that the conventional wisdom – what is accepted and acceptable – itself change. It is the climate of ideas, what is socially acceptable, that ultimately, over the long run, sets the context for the formal and informal institutions that create the incentives which influence behaviour, and thus outcomes.

that generate social and political outcomes. This is not a one way, top-down process. Institutions shape the structure and patterning of incentives, which in turn, over the long run, are shaped by ideas. Institutions are both the product of, and in turn shape, ideas and what is socially and politically ‘the conventional wisdom’ – until ideas have shifted to the extent that the conventional wisdom – what is accepted and acceptable – itself change. It is the climate of ideas, what is socially acceptable, that ultimately, over the long run, sets the context for the formal and informal institutions that create the incentives which influence behaviour, and thus outcomes.

Politics, politics and more politics

We have also learned that the success or failure of development programs is largely determined by domestic politics within aid partner countries. Any self-respecting development practitioner will confirm this. Successful programs align with the interests of powerful actors who can create enough reform momentum, and/or ensure implementation happens with minimal disruption from opponents. Failed projects tend to ignore political dynamics, by pushing for changes that are not politically feasible or assuming that capacity and technical knowledge will be enough to change deeply entrenched political or bureaucratic norms.

Recent critiques of international development have provided compelling evidence that politics is the critical missing in international development assistance. Politics shapes the economic and social choices that determine state trajectories, either leading to effective institutions or cycles of conflict and low growth.

Changing aid operations to be more politically sophisticated has proven to be much more difficult than the analysis. Despite an explosion of high quality analytical work on political-economy, we have seen very few examples of successful application of this analysis towards improving development impact. The reality is that most aid remains staunchly technocratic, inflexible, and averse to the types of operating approaches that could translate political-economy knowledge into impact. Within several development donors, there is a growing concern as to whether analysis has been translated into better operations and impacts.

…Now, if you are still reading—you deserve a prize—and may want to flick to our next blog for ‘orthodoxy’ on governance and development… which we hope (expect) you will either confirm or contest.

[1] King Henry II. In November 2000, in the completely awful UK TV quiz show ”Who Wants to be a Millionaire?”, one contestant answered this question correctly. It was her very last question, and won her one million pounds.

[2] David Cameron speech to Oxfam, June 29, 2006. Available at: http://www.conservatives.com/News/Speeches/2006/06/Cameron_Fighting_global_poverty.aspx. Accessed on 8 April 2012; David Cameron description of ‘One World Conservatism’, 13 July 2009. Available at: http://www.conservatives.com/News/Speeches/2009/07/David_Cameron_One_World_Conservatism.aspx. Accessed on 22 April 2012; David Cameron’s speech at the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation conference, 13 June 2011. Available at: http://www.number10.gov.uk/news/speech-at-vaccine-summit/ . Accessed on 8 April 2012; David Cameron speech at the London Family Planning Summit, 11 July 2012. Available at: http://www.number10.gov.uk/news/prime-ministers-speech-on-family-planning/. Accessed on 10 October 2012.

[3] David Cameron speech at the London Family Planning Summit, 11 July 2012. Available at: http://www.number10.gov.uk/news/prime-ministers-speech-on-family-planning/. Accessed on 10 October 2012.

[4] William Evans and Clare Ferguson, DFID Research and Evidence Department. “The research evidence and a ‘golden thread’ of international development: a literature review”. Undated but probably circa 2013.

[5] For a forensic discussion of how these states emerged see Francis Fukuyama “The Origins of Political Order and Decay”, 2014.

[6] Douglass North “Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance”. CUP 1990.

[7] See the first chapter of “Why Nations Fail” by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson for a clear demonstration of this.

[8] Wayne Leighton and Edward Lopez ‘Madmen, Intellectuals and Academic Scribblers: The Economic Engine of Political Change’, Stanford Economics, 2013

uh…. So what is this governance thing anyway?? You jumped right into debunking the “Golden Thread” myth, and the need to take politics into account when doing development.

“For the [World] Bank, “governance” encompassed three different aspects:

first, the form of political regime;

second, the process by which authority is exercised in the management of a country’s economic and social resrouces for development;

and third, the capacity of government to design, formulate, and implement policies.”

http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/research/researchcentres/csgr/news/doctoral_workshop_on/maldonado_nicole_paper-final_ii.doc

“Governance is a broader term than government. Although it still has no settled or agreed definition, it refers, in its widest sense, to the various ways through which social life is coordinated. Government can therefore be seen as one of the institutions involved in governance; it is possible to have ‘governance without government.'” Heywood (Politics, 3/ed. 2007)

LikeLike

If by good government folk mean something that mimics the current western european model then yes it is not a precursor to development.

However, the converse is also nonsense i.e.bad governments lead to development – as is implied by reverse logic.

The poblem is that few folk are willing to contemplate or accept that models of governance that differ from the western norms can be good because notions of what is good and bad in development are muddled and intertwined with moral, religious and philosophical biases.

LikeLike

Great blog (although I’m not sure you answered the question you set yourself).

The pyramid got me thinking about different entry points for foreign intervention/assistance.

Should we just tackle the problematic outcomes and hope that a heathier, more educated citizenry will eventually drive more substantive change?

Should we focus on changing incentives by establishing alternative/competing institutions that reward ‘good’ behaviour and punish ‘bad’?

Should we focus on changing existing institutions by working with like-minded groups and individuals to change laws and challenge social norms?

Or should we focus on influencing people’s ideas through relationship building and presenting aternative visions of the future?

I’m sure all four have a place. It’ll be interesting to see how the new FCDO strikes a balance between them.

LikeLike