Graham Teskey, Global Lead for Governance, Abt Global

* This article was originally published as a chapter in the Elgar Companion for the World Bank, 2024.

Introduction

A case can be made that 2007 to 2014 marked the high point of ‘governance’ in development. In academia, a number of influential books were published highlighting evidence which demonstrated that capacity and technical knowledge alone were insufficient to change entrenched political interests and bureaucratic norms. These critiques demonstrated that an understanding of power asymmetries is frequently the missing ingredient in project design and implementation. Eminent thinkers looked at the difference between success and failure in development, and all pointed to the primacy of domestic politics.[1]

One of these publications is particularly noteworthy: Development Aid Confronts Politics: The Almost Revolution, by Thomas Carothers and Diane de Gramont, published in 2013. This book sought to explain why development assistance had failed to take politics into account and what could be done about it. The book gave legitimacy to arguments that economics and economists held too much sway.

At the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, the idea of Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) was published in 2012 in a Centre for Global Development paper[2] by Matt Andrews, Michael Woolcock and Lant Pritchett. This led to Harvard University hosting a meeting in October 2014 considering ways of ‘Doing Development Differently’ (DDD). The ‘Harvard Manifesto’ produced as a result of this meeting has been signed by more than 400 development thinkers.[3] The opening two paragraphs of the manifesto summarize the problem: successful programs need to align with the interests of powerful actors who can create enough reform momentum and can ensure that implementation happens with minimal disruption from opponents. If such ‘political will’ does not exist for a project or reform initiative, they unlikely to happen.

This line of academic enquiry was mirrored in bilateral donors which were struggling to find ways to reflect the primacy of politics. What became known as the Thinking and Working Politically (TWP)[4] Community of Practice (CoP) was established at a meeting of Governance Advisers working for the United Kingdom’s Department of International Development (DFID) on South and South-East Asian countries, held in Delhi in November 2013. The CoP was never designed to be a formal organization. Participants at the meeting envisaged a loose grouping of practitioners coming together to share experience of ‘thinking and working politically’ and to create a ‘safe space’ where challenges could be discussed. That remit remains the case. Since the Delhi meeting, a Steering Committee has been established (of between eight and eleven people), with two co-chairs, to guide the CoP, manage the website, and propose meetings as and when possible. Anyone can join and no fees are payable. Since 2013 ‘TWP’ has entered the lexicon of mainstream development; the CoP ‘membership list’ has expanded to more than 300 people; a Washington DC chapter has been established; and the CoP has been granted modest funding from DFID’s successor, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

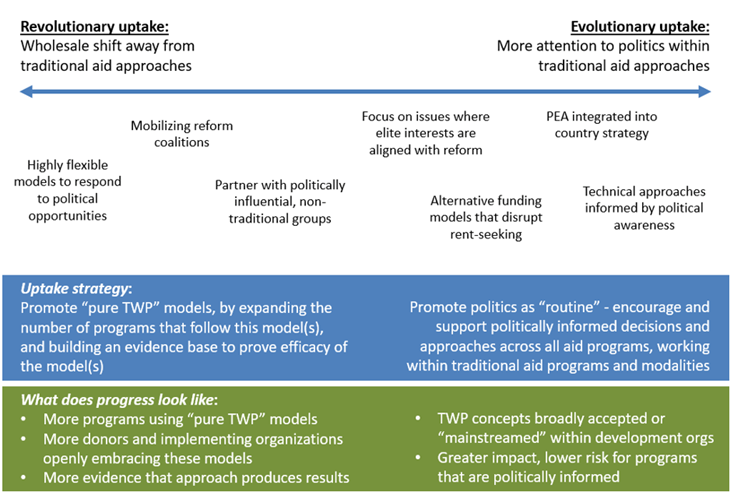

The purposes of the TWP CoP were three-fold: to explain TWP to non-governance development colleagues; to collect and collate evidence on those programs that were attempting to put TWP ideas into practice; and to provide a forum for sharing successes and failures. At heart, TWP is about a different way for donors to undertake their business. Three key differences are central. First, the vertical logic of the logical framework (the logframe) is to be replaced by a flexible approach whereby activities to be funded and outputs to be delivered are not fixed in advance; rather they are to be identified and revised as implementation proceeds. Second, emphasis is placed on understanding the theory of change underpinning the investment: what change is politically feasible? Why do we believe the change proposed will be acceptable to political and bureaucratic elites? Third, stakeholders to be involved in any investment is to be wider than in ‘traditional’ investments, requiring engagement outside of the state and prioritising coalitions for change, rather than relying on key individuals located in the executive. Figure 1 summarizes the difference between traditional and ‘TWP’ approaches.

Figure 1: Traditional and Adaptive Programming (Source: author)

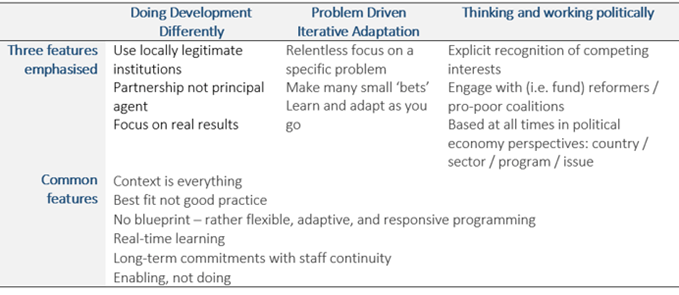

The CoP recognized that this would be a challenging agenda for aid donors. It confronted established ways of working, where objectives and goals were identified in advance, and the original ‘blueprint’ was followed slavishly, with little real-time monitoring of progress or context. One of the founder members of the CoP proposed a spectrum of TWP investments (Figure 2). At one end was an ‘evolutionary’ approach, seen as the most likely to be adopted by donors. Here, investment designs were underpinned by political economy analysis, and a premium was attached to ensuring the investment was politically feasible. Forward budgets contained a degree of flexibility. In short, this end of the spectrum applied to ‘traditional ‘projects, but which required greater political insight in order to be effective. The other end of the spectrum described programs that are fundamentally opportunistic, responding to sudden windows of opportunity, and are focused mainly on policy reform. The quintessential example of such initiatives is the ‘Coalitions for Change’ program in the Philippines, implemented by The Asia Foundation (Sidel and Faustino, 2019). While some development programs have sought to replicate this model the emphasis of most TWP practitioners to this day has been on evolutionary uptake.

Figure 2: The TWP Spectrum (Source: Tom Parks, original TWP flyer)

The evolution of World Bank thinking

There is evidence that some staff in the World Bank had been thinking about the implications of political economy over the previous decade. An internal learning group in April 2008 noted that “the Bank has not yet found an effective approach to assist fragile states in developing their core public sector governance. There is a need for greater technical elaboration of options for content and sequencing core governance reforms and for a better understanding of the politics of the country”[5] (emphasis added). Two months later, the Bank’s Quality Assurance Group reported that: “More thought needs to be given to relating projects to stages of public sector reform, getting sequencing right and ensuring reform programs do not attempt transformations that the underlying governance conditions do not support”[6] (emphasis added). This is a critical statement: attempting “transformations that the underlying governance conditions do not support”. This is Bank speak for political economy. These two quotes acknowledge that staff in the Bank needed to ‘think and work politically’ – i.e., to appreciate ‘the underlying governance conditions.’

The Bank published its first Governance and Anti-Corruption (GAC) strategy in 2007. In 2011, the World Development Report on Conflict, Security and Development presented a compelling case for urgent and innovative responses to fragility and conflict. In 2012 the Bank published an updated GAC Strategy and Implementation Plan which noted that: “Despite the significant progress made over the last few years, it is clear that the Bank needs to do even better in understanding issues of governance, institutions for development effectiveness… It is insufficient to stress economic governance alone.” Staff in the Public Sector Governance Group took this at face value and investigated how to apply political economy analysis in an organization noted for its Articles of Agreement which forbids it from taking ‘politics’ into account in decision making. This culminated in the publication of ‘Problem-Driven Political Economy Analysis: The World Bank’s Experience’ in 2014.

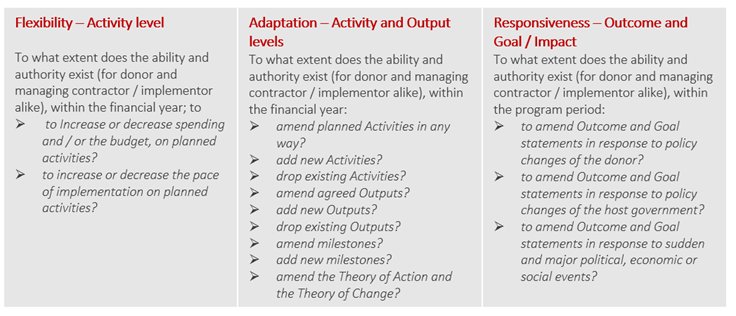

Alphabet soup

These developments came to be represented by three sets of abbreviations: DDD, PDIA, and TWP. Although all were concerned with the same issue (underlying governance concerns) each emphasized slightly different aspects of the ‘thinking politically’ agenda. This is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3: DDD, PDIA, TWP (Source: author)

The PDIA agenda proved more challenging to operationalise than TWP. This is because at its core was the proposal to ‘make a variety of small bets” and see which ones pay off and which ones don’t. For bilateral donors – let alone the World Bank – this required gambling on development (to steal the title of Stefan Dercon’s recent book[7]) and was unlikely to be taken seriously. TWP, at least in its evolutionary guides, was not out of the question.

In 2018, the TWP CoP was independently reviewed by Oxford Policy Management, a consultancy firm, commissioned by DFID. The purpose of the review was to take stock of developments of the TWP CoP in order to assess what works and what could be strengthened in terms of operational practice. The review identified three key achievements: first, support to the establishment or affiliation of working groups within the CoP; second, the production of evidence papers which began to aggregate data and generate lessons learned; and third, the establishment of a website providing key information and resources for new members.

Prior to its abolition, DFID made a number of significant commitments to TWP, both conceptual and practical. In March 2019 DFID published its ‘Position Paper’ on governance (DFID, 2019). The paper identified four ‘shifts’ in its governance positioning. First was the adoption of TWP ‘across all our initiatives’ – not just so-called ‘governance’ programming. Two reasons explain DFID’s choice of TWP rather than PDIA: first, two or three DFID members were on the TWP Steering Committee, and second, TWP was perceived as more operationalisable than PDIA.

The changed context since 2014

The context for ‘TWP’ could not be more different today than it was in 2013. The geo-political environment has changed fundamentally. China has continued its rise to the extent that we are once again living in a bi-polar world, even if it is, at the moment at least, an asymmetrical bipolarity. National interests dominate. The domestic political economy in most donor countries (Scandinavia excepted) is barely supportive of aid, and mutually exclusive narratives have emerged: Black Lives Matter and decolonizing aid on the one hand, and the populist sloganeering of Global Britain and America First on the other. Post-Iraq, post-Syria, post-Afghanistan, the West’s state-building agenda is dead. The UK now spends 29% of its bilateral Overseas Development Aid budget on housing refugees and asylum in the UK.[8]

The difference in the national context for most bilaterals is also very different. In 2013 DFID was admired for its consistency, coherence, and technical excellence. In Australia AusAID was modelling itself on DFID, and a number of ex-DFID advisers were recruited as AusAID sought to transform itself from a project factory into a serious development organization. This ended in September 2013 following the election when AusAID was abolished, literally overnight. Specialist skills were deemed unnecessary, and hundreds of years of development experience walked out of the door, and many technical experts were sacked.

In the UK in 2020 the Department for International Development was swallowed up by the Foreign Office. Even ‘The Economist’ in its July 29th, 2023, issue admitted that the ‘merger’ has not gone well. To some observers, the newspaper noted, this represented “a hostile takeover by right-wingers bent on gutting the development corps” (page 35). The UK has given up its leadership position on development thinking and practice, leaving little room for innovation and new approaches to spending a declining budget.

Meanwhile in the World Bank the Jim Yong Kim years (2012 – 2019) were spent re-organizing the Bank’s internal structure. The effort and resources required to restructure an organization as complex as the World Bank, with over 170 offices all over the world, a tradition of a high degree of decentralization, and any number of competing professional fiefdoms, are hard to underestimate. Furthermore, as many Bank staff were being ‘let go’ over these years, those that remained were concerned more with securing continued employment than promoting ways of doing business than ran counter to the norm. Despite the regular publication of the Bank’s annual World Development Report, there remains a sense (to this author at least) that the Bank too is now no longer the major thought leader on governance that it once was.

Ten lessons in ten years

This section identifies ten lessons divided into macro- and micro-level observations. The three macro-level observations focus on the relationship between TWP and the geo-strategic context in which development is situated, while the seven micro-level considerations focus on the way individual investment projects and programs are designed and delivered.

Lesson 1: TWP (and DDD) have been overwhelmed by changes in the international context

As noted above, international relations have changed fundamentally since the TWP CoP was established. With the return of a more competitive international system, national interests now trump values. Project-level TWP has got overwhelmed in this maelstrom. Developmental impact resulting from investments are less important than their visibility and their ability to woo political elites in partner countries.

Here though there is a distinction between the World Bank and many bilateral donors. The World Bank is protected by its Articles of Agreement ‘to take politics into account’ and thus has not been driven to change the geographical spread of its investments or to reduce its focus on growth and poverty reduction. Its processes and procedures may have prevented it from adopting a TWP approach at the project or program level, but its institutional status and remit have protected it from engaging fully in the game of geo-strategic competition.

Lesson 2: The organizational culture and ‘DNA’ of the World Bank and bilateral government aid departments have implications for their interest in, and ability to, ‘think and work politically’

For all the rhetorical support for TWP in policy documents, program designs, and requests for tenders, it is not possible to argue that it has been translated into practice through changed operational systems. The impact of the abolition of AusAID was thoughtfully considered by Moore (2019), where he dissects the implications of the rejection of technical specialists. It may be too early to tell what is happening in the FCDO, but it is questionable whether the commitment made in DFID’s 2019 ‘Governance Positions’ paper will be honoured.

Lesson 3: The practice of TWP (and indeed DDD) has not been localized

The ‘second orthodoxy’ has failed to escape from its Western aid department confines. There remain few national actors influencing the debate and proposing alternative, locally appropriate methods, or more flexible and adaptive ways to program and project implementation. The 300 or so members of the TWP CoP are overwhelmingly from the global north.

Lesson 4: TWP is now commonplace, but not common practice

Many bilateral donors (although not the World Bank) use some form of TWP rhetoric in their documentation. There is a recognition that TWP ‘makes sense’ – clearly, so-called blue-print approaches to planning are redundant. Yet translating the ‘Thinking’ (mainly one-off studies of political economy) into coherent ‘Working’ remains a distant aim. With foreign affairs departments taking over aid agencies, the space for TWP at the project level has shrunk. There is less patience for considering the nuance of inhibiting factors on project success – what Andrew Natsios once referred to as the ‘frenzy of results’ (the pressure to achieve tangible and easily quantifiable results) remains in place (Natsios, 2010). The irony is of course that TWP at the macro level has expanded: aid programs in their entirety are now being used for political purposes.

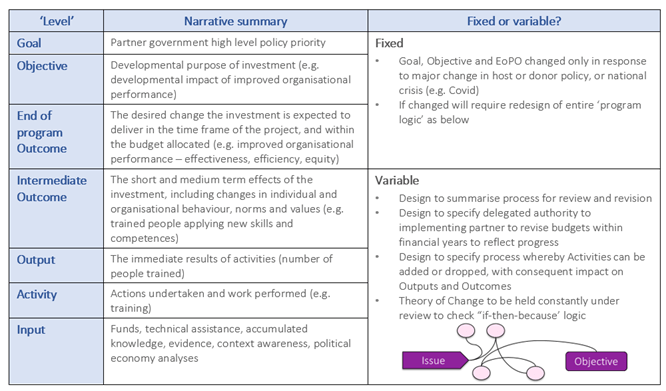

Lesson 5: Where successful at the project level, TWP has metamorphosed into Adaptive Management in practice

Talking about ‘adaptive management’ (AM) appears to be more acceptable to aid departments than TWP. ‘Management’ carries a technocratic ring and proven ways of working. If AM can operationalize the insights of thinking and working politically, then it is to be welcomed.[9] Adaptive management has three elements: flexibility, adaptation, and responsiveness. These terms represent different management techniques and are shown in Figure 4. It could be argued that AM represents the ’Working’ part of the TWP agenda, whereas ex ante political economy analysis is the ‘Thinking part’.

Figure 4: Adaptive management (Source: author)

Lesson 6: TWP has struggled to convince sector colleagues

Incorporating TWP into sector-specific initiatives has proved harder than envisaged. There are many explanations for this. It can be seen as irrelevant, or that asking difficult questions about political feasibility may reduce the chances of ‘our project’ being approved: political economy tells us all the things that may go wrong without providing any guidance about how to improve the likelihood of success.

Lesson 7: Organizational structures and staffing for implementing TWP projects have to be specifically tailored

The literature and practice of TWP and AM use terms interchangeably and uncritically (see lesson 5 above). Practice has shown that it is adaptation that poses the major challenges to TWP: the ability to change course as implementation proceeds. Why should this be the case? It is because adaptation in program delivery requires four functions to be delivered simultaneously:

- implementation: the day-to-day, week-to-week task of delivering activities (how are we doing on physical progress?);

- monitoring: the regular and frequent checking of progress towards achieving outputs (are we on track against the plan, the budget – and most importantly – against outputs and possibly outcomes?);

- learning: our internal and reflexive questioning of progress – what are we learning about translating inputs and activities into outputs and outcomes (what is working and what isn’t?); and

- adapting: revising our implementation plan, adding unforeseen activities, and dropping others, changing the balance of inputs, be they cash, people or events etc. (how are we changing the plan?).

The critical point is that only if we learn as we go can we adapt in real time: this requires delivery (implementation), data collection (monitoring), learning (reflection) and adapting (changing) to be undertaken simultaneously, not sequentially. And here we encounter constraints in organizational (program management) design. Often the responsibility for monitoring is given to structurally separate functional units, far removed from operational delivery and implementation. This is particularly the case with programs funded by bilateral donors but is less so with World Bank programs. That said, most monitoring is undertaken ex post, rather than in real time. Effective adaption and TWP requires monitoring and learning responsibilities to be co-located with implementation teams.

Lesson 8: TWP has to be incentivized by donors at the procurement and design stages, then enabled at delivery.

TWP and Adaptive Management will not just happen. They have to be thought about and planned for at the procurement stage, and contracts have to be designed in such a way as to incentivize adaptation. The donor must authorize levels of delegated financial authority to the implementing agent, otherwise adaptation will get snarled up in what is usually a sclerotic bureaucratic decision-making process.

Lesson 9: TWP has led to a greater appreciation of formal and informal sources of knowledge

The demand for contextualized local knowledge is now more widely recognized and endorsed. This has gone beyond the need for ex ante political economy studies and includes the recognition of tacit knowledge and local relationships and networks.

Lesson 10: Diplomatic colleagues and senior officials remain unpersuaded by TWP

Diplomats consider it self-evident that development is political but remain unpersuaded that it requires the design of an administrative system to make it work.

Prospects

It is difficult to be positive about the prospects for TWP. Donor processes and systems have proved resistant to change. Three things may need to happen if TWP is to prosper: First, donors must reflect their rhetorical commitment to working adaptively with a more enlightened approach to program logic. At the minimum, donor requirements regarding ‘program logic’ should enable the operationalization of ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ approaches. Figure 5 summarizes the minimum requirements of a ‘TWP program logic’. Two elements are critical: first, that donors understand the difference among flexibility, adaptation, and responsiveness; and second, that their systems enable adaptation. This means that while the goal or the objective of the investment remains constant, the choice of specific activities will be determined as implementation proceeds.

Figure 5: A program logic table for TWP (Source: author)

Second, practitioners must redouble their efforts to provide examples and evidence of where such approaches have been effectively applied. This was one of the reasons why the TWP CoP was established in the first place. This is not the same as calling for evidence that TWP has led to success where traditional approaches have failed (the problem of course of the counterfactual), but it does require critical assessment of the circumstances in which a TWP approach was put in place, what it achieved, and what were the factors that led to the effective application of the process.

The challenge may be deeper than this. There has to be a commitment to, and a patience for, funding research that can accompany and observe projects / programs / initiatives over the long term in order to have a real opportunity to observe what may have changed, how and why, and how TWP may have made a difference.

Third, there needs to be a more conscious and explicit effort to apply TWP to current and urgent thematic issues of our time. For the UK this may be climate change. For Australia it may be climate change in its near neighbourhood in the Pacific islands. The task will be to demonstrate the relevance of TWP to the success of the investment – and thus to the reputation of the donor. Unless these conditions are met, donors and the World Bank are likely to continue Thinking and Working Apolitically.

Bibliography

Acemoglu D and Robinson J (2012) ‘Why Nations Fail’. New York. Crown Books

Andrews M (2013) ‘The Limits of Institutional Reform in Development’. New York. Cambridge University Press

Andrews, M., Pritchett, L. and Woolcock, M. (2012). ‘Escaping capability traps through Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA).’ Working Paper 299. Washington, DC. Center for Global Development

Brown, E., Haines, R. and O’Neil, T. (2018). ‘Putting gender into political economy analysis: Why it matters and how to do it.’ From Poverty to Power (FP2P). https://oxfamapps.org/fp2p/putting-gender-into-political-economy-analysis-why-it-matters-and-how-to-do-it/

Carothers T and de Gramont D (2013) ‘Development Aid Confronts Politics: The Almost Revolution’. Washington DC. Carnegie Endowment

Dercon S. (2022). ‘Gambling on Development Why Some Countries Win and Others Lose’. Hurst publications

DFID. (2019). ‘Governance for growth, stability, and inclusive development.’ DFID Position Paper. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/786751/Governance-Position-Paper2a.pdf

Fritz V, Levy B, and Ort R (eds, 2014). ‘Problem Driven Political Economy Analysis: The World Bank’s Experience.’ World Bank. Washington DC

Fukuyama F (2012) ‘The Origins of Political Order’. New York. Farrar. Straus, and Giroux

Fukuyama F (2014) ‘Political Order and Political Decay’. New York. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux

Green, D. (2018). ‘How can a gendered understanding of power and politics make development work more effective?.’ From Poverty to Power (FP2P). https://oxfamapps.org/fp2p/how-can-a-gendered-understanding-of-power-and-politics-make-development-work-more-effective/

Moore, R. (2019). ‘Strategic choice: A future-focused review of the DFAT-AusAID integration.’ Melbourne: Development Policy Centre (ANU). https://apo.org.au/node/223736

Natsios, A. (2010). ‘The clash of the counter-bureaucracy and development.’ Washington, DC. Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/clash-counter-bureaucracy-and-development

North D, Wallis J, and Weingast B (2009) ‘Violence and Social Orders’. New York. Cambridge University Press

Oxford Policy Management. (2018). ‘Review of the Thinking and Working Politically Community of Practice.’ Oxford.

Rocha Menocal, A. (2014). ‘Getting real about politics: from thinking politically to working differently.’ London. Overseas Development Institute.

Rodrik R (2007) ‘One Economics, Many Recipes’. Princeton NJ. Princeton University Press

Sidel, J. and Faustino, J. (2019). Thinking and Working Politically for development: Coalitions for change in the Philippines. Pasig City. The Asia Foundation.

Swift, S. (2018). ‘Blog Series on Thinking and Working Politically and Inclusively.’ USAID Learning Lab. DCHA/DRG. https://usaidlearninglab.org/library/blog-series-thinking-and-working-politically-and-inclusively

Teskey, G. (2017). ‘Thinking and Working Politically: Are we seeing the emergence of a second orthodoxy?’Governance Working Paper Series. Issue 1. Abt Associates.

Teskey, G. (2020). ‘Thoughts on the demise of DFID – a governance adviser’s perspective.’ Abt Governance and Development Soapbox; Forum for thinking and action in international development. https://abtgovernance.com/2020/06/29/thoughts-on-the-demise-of-dfid-a-governance-advisers-perspective/

Teskey, G. and Tyrrel, L. (2021). ‘Implementing adaptive management: A front-line effort. Is there an emerging practice?’ Working Paper 10. Abt Associates. https://abtgovernance.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/abt-associates_adaptive-management_a-frontline-effort_digital-1.pdf

[1] Rodrik (2007); North, Wallis and Weingast (2009); Fukuyama (2012, 2014)); Acemoglu and Robinson (2012); Andrews (2013); Carothers and de Gramont (2013)

[2] Andrews, Pritchett & Woolcock. (2012)

[3] Online, with signatories, at http://buildingstatecapability.com/the-ddd-manifesto/

[4] The origin of the phrase ‘TWP’ can be traced to Stefan Kossoff, a Senior Governance Adviser in DFID, who in 2009 circulated an internal paper entitled ‘A Note on Thinking and Working Politically’.

[5] Rapporteur’s Report (2008). “Strengthening Core Public Sector Functions in Fragile States: Lessons and Challenges from Implementation”. PRMPS / OPCS Learning Event, 1 April 2008, p 1.

[6] World bank Quality Assurance Group (2008). “Improving Public Sector Governance Portfolio: Quality Enhancement Review” p iii.

[7] Stefan Dercon. 2022. ‘Gambling on Development Why Some Countries Win and Others Lose’. Hurst publications

[8] Patrick Wintour. ‘UK using more of its aid budget to house refugees than most donors in OECD’. The Guardian, 12 April 2023

[9] Teskey, G. and Tyrrel, L. (2021)