Graham Teskey, Principal Lead for Governance, Abt Global 1

“The ideas of economists and philosophers… are more powerful than is commonly understood. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority… are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler… I am sure that the power of vested interests is greatly exaggerated when compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas.” John Maynard Keynes. ‘The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money ‘quoted in ‘Madmen, Intellectuals and Academic Scribblers: The Economic Engine of Political Change.’ Wayne Leighton and Edward Lopez. Stanford, 2013

Introduction and background

Once upon a time governance was not a thing in development. It was only about thirty years ago that the ideas of a few academic scribblers began to filter into the development discourse and challenge the contemporary economic orthodoxy – the Washington Consensus. About that time – January 1996 – I joined a new department in the UK’s Overseas Development Administration, the forerunner to the Department for International Development (DFID). It was called the Governance and Institutions Department, or GID.

The work of GID was given a shot in the arm (and professional credibility) a year later when the World Bank published its 1997 World Development Report (WDR) ‘The State in a Changing World.’ This report asked a set of big questions about the nature and functioning of states: why do some states perform better than others, even when constraints, resources, and opportunities are similar? It proposed the simple, yet at the time in development, a counter-cultural recommendation that the role of a state must be predicated on an assessment of its ‘reach’: i.e. its ability to deliver the expected functions of a state (law and order, basic education and health, transport infrastructure).[2] GID turned its attention to this question.

I was thus introduced to many ideas, some of which are now commonplace. There was something in these ideas that resonated powerfully with me. They have stuck with me ever since. They have never been far from my thinking in the work I have been privileged to undertake for DFID, the World Bank, Australia’s Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade, and now for Abt.

The purpose of this note is to summarise six of these ideas – three big ones and three smaller ones – and to explain why they matter for development. Even after 30 years these six ideas seem a relevant as ever. They also seem – dare I say it – to be entering the mainstream of development thinking. As Keynes said, ideas do have this habit of gradual encroachment.

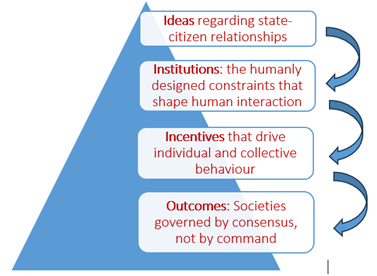

The three big ideas are first, institutions, second, that the relationship among ideas, institutions, incentives, and outcomes matters, and third, the idea of the political community.

(1) The first big idea was – of course – institutions

Today it seems remarkable that we did not understand the importance of institutions. But we didn’t. (Well, I didn’t anyway). But remember this was 15 years before Acemoglu and Robinson told us why nations fail, and a full 25 years before Stefan Dercon (an ex- DFID Chief Economist, no less) ventured into the world of governance by talking about gambling. He was listened to in a way that us governance types never were. After all, he was an economist.

The early days of GID was focused on two areas of work. The first was organisational development – what was it that made organisations function, and how could we, a bilateral donor, help? This work mirrored the work of management consultants, and we dabbled with management theories and management jargon. We could all speak business process reengineering (some of us still can). This strand of work was overtaken by questioning the nature and functioning of the state after the 1997 WDR was published.

In those days, each professional grouping in DFID would hold an annual ‘retreat’ in order to reflect upon our work and learn from each other and from outsiders. Outsiders were usually influential academic scribblers who would be invited to speak to the group (which by then numbered about 60 or 70 people). One such scribbler talked about the work of someone called Douglass North on the role of institutions. North had won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1993 and had published his most famous (and accessible) book in 1990: ‘Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance’.[3]

I dutifully bought a copy. The first line of this volume is almost as famous as the first line of Anna Karenina. North says that “Institutions are the rules of the game in a society, or more formally, are the human devised constraints that shape human interaction.” Over time, the phrase “the rules of the game” became a dominant conventional wisdom in development. We know now that there are formal rules of the game (constitutions, laws, rules, regulations) and informal ones (norms, habits, customs, values). We have also learned that often these informal rules are more influential in determining individual and collective human behaviour than are the formal rules.

Once I understood this, other things followed. First, I realised that the rules of the game create powerful sets of incentives to which people, individually and collectively, respond. Given human nature and the urge to survive and thrive, the usual human response is to protect or extend one’s own interests, rather than to promote the public good. Up to that point I had naïvely believed governments existed to promote the common weal. I was learning to become more cynical, as Julian Baggini, the British philosopher urges us all to be.

Second, I realised that this thing called the new institutional economics (which is what it was called) could help explain what was going on in the real world. It could help explain why some democracies generate and persist with policies that are wasteful and unjust (think health care in the US); why some failed policies persist over long periods of time even though they are known to be socially wasteful and unjust (think fuel subsidies in Indonesia and Nigeria); and why some wasteful polices get repealed (think airline deregulation) and others don’t (think sugar subsidies and tariffs).

Why does this matter?

The importance of institutions and the incentives they create seem now to be so obvious that they should not need saying. But they do. Bilateral agencies spend billions each year on technical assistance in pursuit of ‘capacity development’ objectives. The logic is that that improving the formal rules of the game – systems, processes, rules, and regulations – will, when combined with some judicious ‘capacity development’, improve the quality of decision making, resource allocation, and development outcomes. This may sometimes be the case, although the evidence for it remains scant even after thirty years of searching. More often than not interests trump values. The institutions that drive behaviour in many partner countries are the informal ones that prioritise private gain over public interest. Donor rhetoric acknowledges the importance of these institutions, but we seem to turn a blind eye to the malevolent informal ones.

(2) The second big idea followed from the first: that the relationship among ideas, institutions, incentives, and outcomes matters

I had never thought about development this way. I was schooled in Cobb Douglas production functions, the savings gap, the investment gap, and other gaps I cannot recall. I worked under the assumption that more capital (‘investment’), when combined with easier trade, would improve production and productivity, and this would somehow seamlessly translate into higher incomes, lower inequality, and reduced unemployment. After all, the late, great, Professor Dudley Seers said that these are the three things that constitute the heart of development.[4]

So, when I discovered the power of institutions, particularly the informality of the ‘unwritten down’ ones to influence if not determine individual and collective behaviour, it came as a shock. By the late 1990s I had been colonised by the idea of these institutions. I had become an institutionalist. (Indeed, when I went for an interview at the World Bank about this time this time I was asked “if I was an institutionalist”). Almost unconsciously, I had lost sight of the power of ideas and of agency. At this time, the governance cadre in DFID did not interact too much with the social development cadre. We could have learned much about agency from them, but each professional cadre in DFID was competing for power and influence, so interaction was limited.

After the UK’s May 1997 election, the ODA was abolished and Clare Short was appointed Secretary of State for International Development in the newly created DFID. Soon after taking over the department, she announced her intent “to change it from a project factory into a development organisation.” She succeeded. Single-handedly (but with support from the department’s most senior staff), she changed the culture, values, and incentives of the department. The irony is that it took me three or four years to realise that I was working in an organisation that had been transformed by the ideas – the agency – of one woman, the remarkable Clare Short. This may sound hyperbolic, but it was the case. I was there four years before she arrived and was there for 13 years after she resigned over the Iraq war. She transformed the organisation. Her ideas created the institution that was DFID.

The new DFID created incentives that motivated staff. We were encouraged to think beyond projects and narrow cost benefit analysis, and to understand the rules of the game and the power of incentives. We were free to identify initiatives that might actually influence the rules of the game and nudge them in a progressive direction – to reduce unemployment and inequality, and to raise incomes of the poot. Under Ms Short, we were encouraged to ‘think and work politically’, although the articulation of this phrase lay ten years in the future.[5]

DFID’s new mission statement and vision were accompanied by a strong set of values, based on Clare Short’s own world view. All DFID investments had to be demonstrably pro-poor. ‘Pro-poor’ became the preferred language – think ‘Poverty Reducing Strategy Papers’ (PRSPs) as demanded by the WB and the IMF. Today, poverty reduction barely registers in the lexicon of bilateral donors. Staff joined DFID because they shared those values, not because they wanted to be civil servants. (Indeed, Clare Short did not want us to be civil servants. On her first day in DFID in her welcoming address, she forbade all staff from talking to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) without her knowledge. How we cheered). Bureaucratic processes became less important. The level of risk tolerance rose. Outcome and impact were what mattered, not ensuring that all the 300 or so pages of DFID’s Operations Manual were followed.

Why does this matter?

It matters because there is a logical relationship among ideas, institutions, incentives, and outcomes. The agency that people have – their ideas – shape (to repeat Douglass North) “the rules of the game in a society, or more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction.” Slavery is an exceptional example of this relationship. Mid-nineteenth century America went to war over competing ideas about the institution of slavery. There existed strong incentives within the southern elite for its continuation (and indeed among mill owners and conservatives in the UK). But the idea that slavery was morally wrong won out, and over time slavery was abolished. Ideas ultimately delivered outcomes, working through institutions which create sets of incentives.

Eventually I came to appreciate that ideas (agency), incentives, and institutions mix together in a sort of holy trinity that sometimes can deliver great development outcomes. This is important for two reasons. First, it is a good way of thinking about development. Formal and informal institutions emerge in all countries for specific historical, political, economic, and social reasons. Development practitioners need to understand how they emerged, and the incentives they have created. Only when we understand this can we practitioners suggest what is developmentally appropriate (whatever the level of ambition) and politically feasible. This is the second reason this broad framing is important. Do we judge that the country’s institutions will support the change proposed? Are there sufficient ‘reform champions’ in place in key positions at the top of the little diagram above with the ideas and the agency to deliver the change? Will they, like Clare Short, be able to change the institutional rules of the game to create incentives for change?

DFAT’s guide to political economy says this clearly: change must be developmentally appropriate and politically feasible. Of course, the hard bit is to judge what will be politically feasible. Assessing the ideas and agency of leaders and the inherited institutional context will take us some way in reaching such a judgement. (It may also require a little bit of knowledge as described in smaller idea #6 below).

(3) The third big idea that I encountered came squarely from anthropology political science – the notion of the united political community

At the time I was working on Africa, and someone said I should read “Power in Africa: An Essay in Political Interpretation” by Patrick Chabal.[6] So I did. Chabal argues that the notion of a community is the most primary of all political concepts. A political community is a group of people who are bound together by a common set of values, and who are governed by a system of laws and rules. Individuals comply with obligations and duties in order to contribute to the common good and maintain stability and order.[7]

Chabal noted that in Africa, unlike in Europe, the state preceded the nation. African states were the creation of colonial powers, were drawn by straight lines on maps. and were imposed on territories where, quite often, there were multiple political communities. These historical processes are still working out in Africa today. States exist. Nations struggle to emerge. In the part of the world where I now live and work, we see this in Papua New Guinea. Chabal suggests that in post-colonial states meaningful political communities emerge as a result of three things: (i) the creation of a shared national vision; (ii) a national organisation – the national party; and (iii) the aggregation of local support for the national party. In sum and writ large: the invention of unity. Where this is absent there is no political community. No shared identify. No nation. When the World Bank invited Francis Fukuyama to visit the Solomon Islands and PNG in 2007, he noted a mismatch between the political structure of the state and the structure of society.[8] In the almost 20 years since then this mismatch has deepened. In academic terms society is now embedded in the state, but the state is not at all embedded in society. Simply put, the way of doing business at the village and clan level (big man status, patronage, clientelism) has colonised the way of doing business at the state level. There is no political community in PNG, and probably neither is there in the Solomon Islands. They are states but they are a long way from being nations.

Why does this matter?

It matters because only where there is a functioning and united political community can there be meaningful political accountability. A political community is defined by the way its members create, re-create, and abide by the principle of political obligation. If there is no political community (or more accurately, many intensely localised political communities) the formal rules of the game (constitutions, laws, rules, and regulations) will be trumped in many different ways in different places by these micro political communities. In these circumstances, called segmentation in the literature, implementing programmatic policies nationally may well be impossible. There is no shared vision and no acceptance by one political community that others have legitimacy. Government will be replaced by fiefdoms, both spatial and organisational. Sometimes these two overlap.

It matters also because we (the ‘we’ being the development industry, donors, managing contractors, CSOs alike) continue to operate as if the countries where we work are functioning and effective nation-states. We design programs to be rolled out by ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs) as if the state is a functioning Weberian bureaucracy. (We also seem to assume that Principal Agent relations – little idea # 4 – operate effectively in every MDA, and all the time wilfully ignoring path dependency – little idea # 5).

These three big ideas may not seem big today. But they seemed big to me then. The issue may be not how ‘big’ these ideas are, but if they are having an impact on contemporary development practice. Answering this goes beyond the scope of this note, but it does raise the question of how and why ideas and concepts wax and wane in development. Institutions seem to have caught on, although the power of informal ones seem so often to be ignored. Development practitioners (and diplomats even more so) put a high value on agency and leadership, but we seem to do so in something of an institutional vacuum. And the political community? Well, this just has never caught on. We treat nations as states and states as nations. Often the terms are used synonymously.

Also at this time, I became aware of three smaller – but equally powerful – ideas: path dependence, Principal – Agent theory, and high and low politics.

(4) Path dependence

The idea of path dependence has two interpretations, one general and one specific. The general interpretation is that history matters, and that current conditions can be understood fully only by a close examination of the past and the events and decisions that have led us to where we are now. (Since Douglass North arrived on the scene in the 1990s, a fully fledged school of ‘historical institutionalism’ has arisen.) Nobody today seriously disputes the importance of history, although sometimes in development we seem to try our best.

The second interpretation is more specific and the one that matters most for development. Path dependence makes a claim about how past events and decisions constrain agency and freedom of action. Once set on a particular course of action, social systems and processes are difficult to change. It is akin to the idea in economics that prices are ‘sticky downwards’: once prices have risen it is difficult for them to fall again – sellers have every incentive not to reduce them. Once development is set on a particular course, the institutions that settle around that course (formal and informal) create incentives and interest groups for their continuation. These institutions reinforce the current development path. Extant institutions create disincentives to change, and interest groups will have a strong stake in their continuation. Institutions are sticky full stop.

Path dependence is applicable at all levels: national, program, and organisational. Changing course nationally (outside of revolution or military coups) is hard. Tony Blair wrote in his biography that after taking office in 1997 he assumed he would be able to deliver the policies the new Labour Government had planned. He found the opposite. Delivering Labour’s policy agenda was impossibly hard: not because of outright opposition, but because the institutions responsible for delivering them were just not able to change in the way he wanted. They were sticky. They were path dependent.

Similarly at program and organisational level. Change by definition generates winners and losers. The losers will not like the change and they may try and resist the change. If they are powerful, then they may be able to prevent the change happening. Think again of health care in the US: the medical profession, hospitals, ‘big pharma’, and health insurance companies were all losers from Obamacare. They were so economically and politically powerful that they were able to prevent meaningful change.

Why does this matter?

This question is simple to answer because change will be contested and too often, we assume it won’t be. Most bilateral development initiatives are designed to work with and through the executive machinery of partner governments. We seek to bring about change in MDAs: to make them more effective and efficient and deliver better outcomes. However, any scrutiny of mid-term reviews and ex post evaluations consistently suggest that we underestimate the challenges to be faced. Path dependence is powerful and real. When DFAT and AusAID were ‘merged’ in 2013 the rhetoric was to bring together the best of the two former departments. But as Richard Moore noted in his 2019 review, the two departmental cultures proved much harder to integrate than envisaged.[9] The same can be said of the DFID and FCO merger of 2020. In summary, path dependence is real and there are strong reasons and incentives why the status quo prevails. Our ‘theories of change’ and our ‘program logics’ need to reflect this. Our designs often ignore these questions, and our project objectives are often too ambitious. We seem to have struggled to learn this lesson – or at least put it into practice.

A more critical argument can be made. It is not that we have not learned these lessons. On the contrary, we have learned these lessons well. The issue is that all major bilateral agencies have reverted (using Clare Short language) to being ‘project factories.’ There are few, if any, transformational ideas to be seen emerging from development ministers or the senior (diplomatic) staff that now run the donor agencies. The incentives driving decision-making in these organisations are to meet national interests (not those of the ‘partner’), to spend the full budget allocation, on time and within the financial year, and with all due processes followed. The core skill required of most aid bureaucrats today is to translate HQ ‘policy’ into procedures, largely focused on checks and balances. It would appear that Thomas Sowell, the famed US economist and political commentator was right when he noted that “you will never understand bureaucracies until you understand that for bureaucrats procedure is everything and outcomes are nothing”. One could further argue that a ‘Trumpist’ transactional perspective now dominates: will this project buy us favour with the host government? What are we getting out of this aid business?

(5) The second smaller idea is Principal – Agent theory

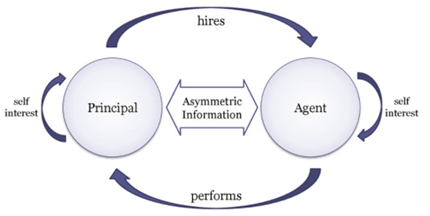

This is a simple yet powerful idea. Formally the Principal-Agent relationship is an arrangement where one entity (the Principal) appoints another (the Agent) to act on its behalf. The Principal hires or appoints the Agent to perform duties they can’t or don’t want to do.

This idea is relevant in many circumstances in development. For example, the minister of a government department is the Principal and her / his staff are the agents, cascading from the Permanent Secretary down to the most junior member of staff. Indeed, in a bureaucracy nearly all staff will simultaneously be Principals and Agents. All staff have a manager (the Principal) and all but those most junior staff will have underlings (Agents). The minister is also an agent – of the prime minister, and of his or her constituents.

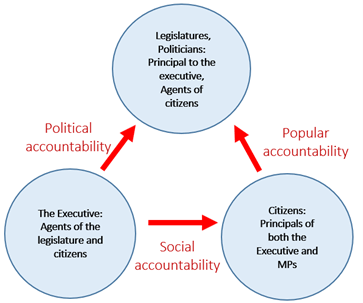

We can apply this idea collectively. As politician are accountable to citizens, they become their Agent. Similarly with regard to the executive: they are accountable to both citizens and minister / the legislature. They are the Agents of both.

Why does this matter?

Principal Agent theory has important implications for two contemporary priorities in development: partnerships and locally led development. Donors now are prioritising ‘partnerships’ with governments. The problem with partnerships and locally led development is that there is one ‘partner’ (the donor) who provides the cash and determines the terms and conditions on which that cash is provided. This partner chooses on what the cash will be spent. The other ‘partner’ – the recipient government, the managing contractor, the NGO – can either take it or leave it. What we have is a Principal – Agent relationship. This relationship as it actually exists lies at the opposite end of the spectrum from ‘partnership.’

Firms like Abt are contracted to be the Agent of the donor (the Principal). In these relationships, we are the Agent (the implementing partner) of the client (the donor) who retains power and authority. There is nothing at all wrong with this: it just is not a partnership. Similarly with respect to locally led development (LLD). Where the donor is the Principal, LLD is almost impossible. In such arrangements the Agent – be they international or local – are not able to exercise any meaningful power and authority. They have no agency.

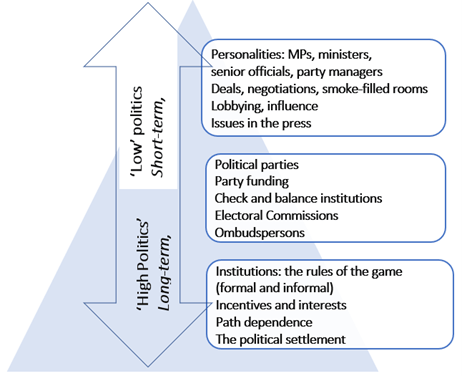

(6) The third smaller idea is the distinction between high politics and low politics

High politics covers matters that relate to the way the states operates and its survival, whereas low politics refers to the day-to-day week to week machinations of the body politic. Both are important, but the two perspectives are different. In the OECD, all development agencies now fall under ministries of foreign affairs. However, their respective governance perspectives differ. Both sides of the house start from a position that politics matters for development. This makes things simultaneously easier and harder. It is easier because diplomatic colleagues know full well that politics matters – they are taken aback at the historical resistance to engaging deeply with political issues on the development side. It is harder because diplomatic colleagues doubt they have much to learn from governance specialists (“after all we have been doing politics for years”).

Diplomatic staff focus on the immediate here and now of politics. They focus on the nitty gritty of political life. Who is in and who is out? Who is in bed with whom (sometimes literally, as in Fiji recently)? Who are the coming men and women? This constitutes the stuff of cables from Posts to HQ. Diplomatic staff are focused on individuals – the powers that be and their networks. This is low politics.

By contrast governance advisers on the development side of the house look at politics structurally: how the political structure affects elite formation, the nature of the political settlement (a big idea that did not really arrive until ten or so years ago) and the nature of the social contract. They look at ‘deep structures’ – the historical institutions that influence if not determine individual and collective behaviour. This is high politics.

At the time of writing (late January 2025) a good example of this would be the political scene in the US. There is much debate about the influence of Elon Musk, and the row over H-1b visas. Will the MAGA view prevail (all immigration must be stopped), or will the financial power of the tech-bros win out (letting in high tech whizz kids from all over the globe)? Which group has Trump’s ear? Who are the key visitors at Mar-a-Lago and now the White House? This is the drama of low politics, and which I am sure is dominating diplomatic cables from DC to concerned capitals all over the world. By contrast, governance analysts and political scientist are reflecting on issues such as ‘negative partisanship’ – the inclination “for people to vote not for a party in which they believe, but against another one that they fear or despise”.[10] This is high politics: the underlying and changing drivers of behaviour. Clearly both matter, but they are subjects of study for different tribes.

Why does this matter?

With all we have learned from the New Institutional Economics regarding the interplay of agency, structure, and institutions, both perspectives are necessary. Diplomatic staff engage daily in politics – talking, briefing, cajoling, persuading, looking out for informants. Governance advisers look for the institutions and incentives that drive behaviour. Unless the two perspectives are married, diplomatic staff will continue to assume that those avowed reform champions waiting in the wings will deliver the change required at the next election. They may do – but the evidence suggests that if they are indeed ‘waiting in the wings’ then they have already been playing within the rules of the game to get where they are now, and this is unlikely to change once in office (think Jokowi in Indonesia).

Concluding with one strength, one lament and a call to action

The strength

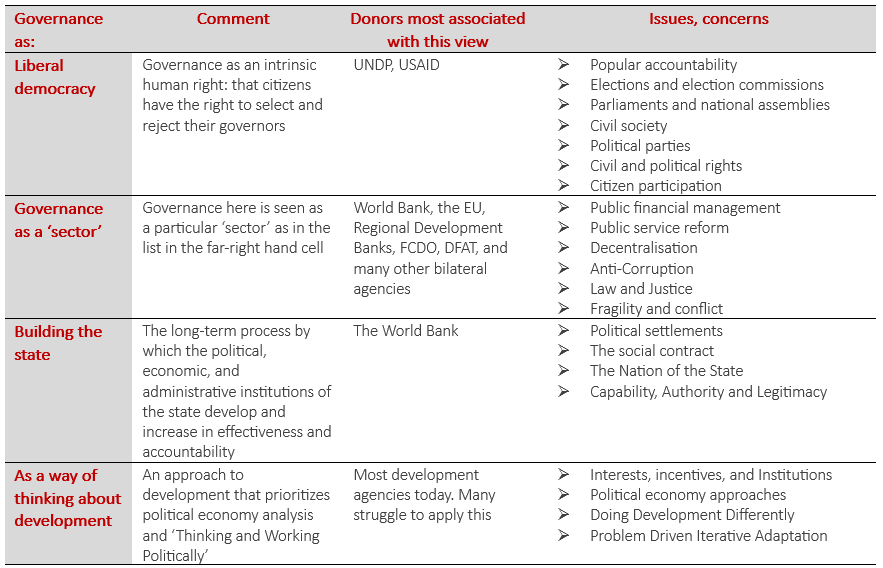

The strength is that it is now the conventional wisdom that effective governance (not ‘good’ governance[11]) is critical to poverty reduction. Here in Australia, at the time Clare Short took on her transformative role in DFID, Alexander Downer, then Minister of Foreign Affairs, announced that “we will make governance a specific focus for Australia’s aid program, for the first time. Effective governance means competent management of a country’s resources”.[12] This has continued ever since. Even today DFAT spends more on governance than any other ‘sector’. This characterises governance as a ‘sector’: public financial management, public service reform, decentralisation, anti-Corruption, law and Justice, or fragility and conflict. There is nothing wrong with this – but it is a limited view.

Since 1997 the understanding of governance has matured. ‘Governance’ has now come to be thought of in different ways. It is not merely a ‘sector’, like education or health. I suggest that there are now four different interpretations of governance, and they are not mutually exclusive. The figure below summarises these interpretations and which donors are most associated with each view.

This is a strength because it articulates the importance of governance ideas and approaches in different aspects of this complicated thing called development. The different interpretations augment the argument of this note that ideas, institutions, and incentives matter.[13]

The lament: loss of intellectual leadership in governance

This leads to me ask where does intellectual leadership for governance in development now lie, and what are the mechanisms for sharing ideas? From around 1995 to 2015 the World Bank provided leadership, with support from DFID. The Bank today seems to have given up its pre-eminent role. Unlike its 1997 predecessor, the 2017 WDR (‘Governance and The Law’) failed to make an impact. It was just so, well, inoperable. Further, the Bank’s internal restructure under President Jim Kim (2012-2019) abolished the Washington department (where I worked) that provided intellectual direction to the governance agenda. The Bank’s corporate ‘Governance and Anti-Corruption’ strategy was discontinued. Many staff left. There remains in the Bank a few brilliant thinkers and doers; some continue here in the region where I now work. But they are lone voices and admit to having no organisational heft back in DC.

Simultaneously in the UK, the right-leaning government elected in 2010 sought serious ‘efficiency savings’ in the civil service, and much policy work in DFID was pared back. This was given a further boost following the FCO’s takeover of DFID in 2020. Today, the Governance cadre in the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO) is reduced to about 60, less than half the number ten years ago. These staff now predominantly work on program design and delivery. The document that dominates the lives of FCDO specialists is ‘The Business Case’: 40-60 pages making the case for the next project. A more egregious cull happened in DFAT after the 2013 ‘merger’. When I arrived in AusAID in September 2012 to take up the position of Principal Governance Specialist there were 39 staff in the governance branch in five teams. In DFAT today the number is 1.5 FTE.

These organisational changes were also accompanied by (some would say driven by) a sense that governance projects do not deliver ‘results’. Is this the case? World Bank research suggests that broad-based public-sector reform projects (governance projects in other words) perform no better and no worse than non-PSR projects. However, unlike straightforward ‘sector’ projects, PSR projects perform better in countries with democratic than autocratic regimes; in more aid-dependent countries than in less; and they benefit from the presence of programmatic political parties. The WB conclusion is that PSM projects are particularly sensitive to, and harder to insulate from, political contexts than non-PSM projects. However, ceteris paribus, as economists like to say, performance is broadly comparable.[14]

As a result of these two trends, there is something of an intellectual vacuum for governance thinking and ideas. Some universities and think tanks have tried to respond to this vacuum,[15] but their work is now harder to ‘socialise’ within formal bureaucracies, as there are few staff members available to perform this task. it. I am aware that this is a doleful conclusion. I take Julian Baggini’s advice above seriously.

If the World Bank and DFID have surrendered their historical role, will academia step up? Straddling the divide between ideas, theories, and concepts on the one hand, and policy, operations, and practice on the other, is not straightforward. Professional scholars dominate the former, and there is no doubt that we practitioners are in their debt. This note has emphasised this. Both ‘tribes’ are interested in, and committed to, similar things, and often use similar language: agency, structure, leadership, norms, values, power, gender, incentives, coalitions, institutions, identity – the list is long. But frequently I get the sense that the two tribes often talk past each other. We inhabit worlds with different incentives and interests. Five come to mind.

First, practitioners, whether they be public servants or consult argue to a decision (“what should we do?”), whereas academics argue to a conclusion (“how did this situation get to be like it is?”). Academics often don’t get to the ‘so-what‘ part. Most bureaucrats and consultants get there too quickly. Second, bureaucrats value judgement. The more senior in the hierarchy, the greater the value placed on judgement. Analysis forms only one part of reaching a judgement. For scholars’ analysis is everything. Third, in bureaucracies, narratives matter. In academia, methodology is pre-eminent. Communications specialists today tell us that stories matter most: they will be remembered long after the statistics are forgotten. Politicians demand a narrative: how does the decision look and feel? This is anathema to scholars: they are searching for ‘truth and wisdom’ for which methodology is critical. Fourth, bureaucracy demands brevity, surety, and simplicity. Margaret Thatcher was known for demanding that briefs be no more than two sides of A4. Academic reputations and tenured positions are not won by brevity and simplicity. Surety can help if the evidence is watertight and the methodology impeccable. Finally, bureaucrats have limited tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. Decision-makers need assurance that spending public money will deliver the prescribed outcomes. By contrast, uncertainty and ambiguity constitute the lifeblood of academic debate.

So maybe the question is not will academia stand up, but can it? How many academics have worked delivering aid programs in complicated and contested environments, with many different incentives acting upon them? I am sure the answer is few. Do academics understand the realities of implementation? This lack of direct experience in the maelstrom of real-world delivery may explain why there is so much development think-tank discussion in Australia about the size of the aid budget and formal government policy – it is easier to write about and critique. It is easier to describe how change occurs broadly, but hard for academics to understand the relationship between the action of a development organisation or implementing agency to create incentives for change, or to assess whether this is even possible. I am not criticising academics: this is just to demonstrate we live in different world and respond to different incentives.[16]

Of course there are many brilliant academics producing stellar work. It was great that Acemoglu and Robinson won the 2024 Nobel prize for economics (“it’s institutions, stupid”). But now there is no organisation in the world that has both the intellectual heft and the lending/granting resources to put ideas into practice. The World Bank had it, as did DFID. Those days are gone.

Despite once spending a few years teaching at a (not very prestigious) university early in my career, I know I am not a professional scholar. But I have always aspired to be a scholarly professional: to bring the ideas of academics and real scholars to the fore in development practice, and to make them accessible and relevant. I am fortunate to have held positions where this was the remit – in DFID, the World Bank, DFAT, and now in Abt. Having now been around the development sector for (sadly) such a long time, today I see few positions such as these that afford the opportunity to reflect on the interaction between ideas and practice. I would note (also sadly) that the positions I held in DFID and in DFAT have been abolished. It is almost as if the formal government / international public sector bodies have given up on the primacy of ideas. It is depressing.

A call to action

What can be done? I would suggest three modest things. None of them are dramatic, but individually and collectively they may make a small difference. First, we need to regain sight of the instrumentality of the state. The Economist newspaper put it succinctly in its January 11th, 2025, edition: “a capable state matters for economic growth” (page 11 of the Africa feature), and – with respect to Africa but the assertion applies globally – “…states are often incapable of doing things they should do while doing plenty of things that should not” (page 10). It is not about the size of the state. It is about what the state does and how well it does it. This was the central argument of the 1997 World Development Report mentioned at the outset of this note. It is about the role of the state and its reach. What the state seeks to do in Timor-Leste will be different to what it seeks to do in Norway.

Second, academics and practitioners need to do a better job of collecting and synthesising evidence regarding the impact of aid in general and ‘governance projects’ in particular. I am concerned that here in Canberra Australian governments of both left and right will continue to minimise aid because most members of the government do not believe development support ‘works.’ While the ideological argument for aid is accepted (“it’s good to help people”), there is scepticism regarding longer-term development programs. Humanitarian budgets (‘aid’) will rise while ‘development’ budgets will either decline or at best stagnate.

The development community (which includes me) has failed to provide compelling evidence of impact. This is something that development practitioners and academics need to demonstrate in order to keep development a live and funded issue. While evidence is there, it is often weak and piecemeal. The examples of where development has not ‘worked’ are more numerous – and they are regularly and gleefully reported in the media.

Third, the major development actors (the FCDO, USAID, the EU, the WB, and DFAT – in this part of the world anyway) should reinvigorate their capability to engage with academia on ideas, and what those ideas mean for practice. This note has tried to demonstrate that it happened before when the WB and DFID were sufficiently confident to take on the ‘institutions’ agenda. There is no reason why, with the right staff in the right positions, this could not happen again.

I would like to finish this note on an optimistic note, but… I am not optimistic about development the way it is being prosecuted today. The problem of course is path dependence. Looking at the donor landscape today it is hard to see from where change may come. Development is not an international or domestic priority in any OECD DAC country. Live Aid in 1985 created global awareness and concern over the Ethiopian famine. Today the civil war and the resultant famine in South Sudan barely gets reported. The world has lost interest. Donors see aid as a means primarily of pursuing their own interests, (”a diplomatic tool”) and certainly not as a means of poverty reduction. The world of course is different to 1997 when DFID came into being. The zeitgeist then was that the world has entered a ‘unipolar’ moment and Francis Fukuyama talked about the end of history. Globalisation would lift all boats. That world is unrecognizable from the one that we now live in: it is described in many ways: ‘strategic competition,’ ‘the return of the Hobbesian world,’ and ‘the promotion of national interests’.

I must add that I have no problem with countries promoting their own interests. But I do have a problem with countries using dwindling aid budgets to promote their own interests rather than address problems of absolute poverty and inequality. I am not naïve about the chances of this happening any time soon. However, even against this background I do believe development agencies can do better. DFAT has rightly called for its development expertise to be deepened and expanded. The FCDO still has about 500 sector specialists. The World Bank has retained staff with real intellectual gravitas. The problem is that at the moment this does not add up to much. Most of these staff work on designing and delivering programs. It would be good if even a few of these competent and committed staff could have the time and space to think about ideas, concepts, and theories, and to engage with our academic colleagues to make more persuasive and influential arguments.

This article was first published on Australian National University’s Dev Policy website on 18 February 2025: 30 years scribbling about governance – Devpolicy Blog from the Development Policy Centre

[1] Thanks to Rosita Armytage, Brigid O’Farrell, and Alan Whaites for comments on early drafts

[2] Alan Whaites. ‘States in Development: Understanding State-building: a DFID Working Paper.’ Unpublished 2008

[3] Cambridge University Press

[4] Seers, D (1969). ‘The Meaning of Development.’ Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex IDS Communication 44

[5] The phrase, I believe, was coined by a current senior staff member of the Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office, now serving as Deputy Head of Mission in a critical east European country

[6] MacMillan, London 1992

[7] Appreciating the importance of a political community is not limited to political scientists. In their history of the emergence of the English State, Caroline Burt and Richard Partington noted that a far savvier King than John (1199-1216) would have “found constructive ways of working with … the embryonic political community”. “Six Kings and the Making of the English State.” Faber, 2024 p 79

[8] Francis Fukuyama. 2007. ‘Governance Reform in Papua New Guinea’ Unpublished mimeo

[9] Richard Moore. ‘Strategic Choice: A future-focused review of the DFAT-AusAID integration.’ 2019

[10] The Economist. ‘The Anti-Politics Eating the West.” Essay. 2nd November 2024 p 19 ff

[11] ‘Good’ governance is a normative term, presupposing both liberalism (privileging freedoms of the individual) and democracy (a particular system of government). ‘Effective’ governance refers to the ability of a state to deliver the things a state is responsible for delivering – both ‘survival’ and ‘expected’ functions. See Whaites again

[12] Speech to the Federal Parliament, November 1997

[13] The three Is. All the tools one needs to be a governance adviser

[14] World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6798. ‘What Factors Predict How Public Sector Projects Perform? A Review of the World Bank’s Public Sector Management Portfolio’. 2014

[15] In Australia, it is the Australian National University here in Canberra and the Lowy Institute in Sydney

[16] And we practitioners are culpable too: have we delivered sufficient evidence that aid works, at project, program, and national levels? Probably not